The Parables of the Barren Fig Tree and The Ten Bridesmaids (or Ten Virgins) are two eschatological parables that our class treated together.

The Barren Fig Tree (from Luke 13) is brief: The owner of the fig tree hasn’t found any fruit on it for three years so demands that it be cut down. The caretaker replies: “Leave it alone for one more year, and I’ll dig around it and fertilize it. If it bears fruit next year, fine! If not, then cut it down.”

The Ten Bridesmaids (from Matthew 25) are waiting for the bridegroom. The five wise bridesmaids brought extra oil for their lamps. The five foolish bridesmaids did not bring oil, left to buy more, and were gone when the bridegroom arrived. “‘Lord, Lord,’ they said, ‘open the door for us!’ But he replied, ‘Truly I tell you, I don’t know you.’” Jesus concluded: “Therefore keep watch, because you do not know the day or the hour.”

The parables address two different failures of discipleship. The Barren Fig Tree is about the failure to bear fruit. As Klyne Snodgrass says, “We do not know when we will be called to account for our lives. We need to recover some sense that our actions really are significant and remember that the gospel includes judgment, mercy, and a call for repentance and productive living” (Stories with Intent, p. 265).

The Ten Bridesmaids is about the failure to be prepared. As Craig Blomburg puts it, “Like the foolish bridesmaids, those who do not prepare adequately may discover a point beyond which there is no return—when the end comes it will be too late to undo the damage of neglect.” (Interpreting the Parables, p. 241)

Although Jesus used both parables to give warning to his contemporaries of imminent judgement, there are clear applications for his Second Coming.

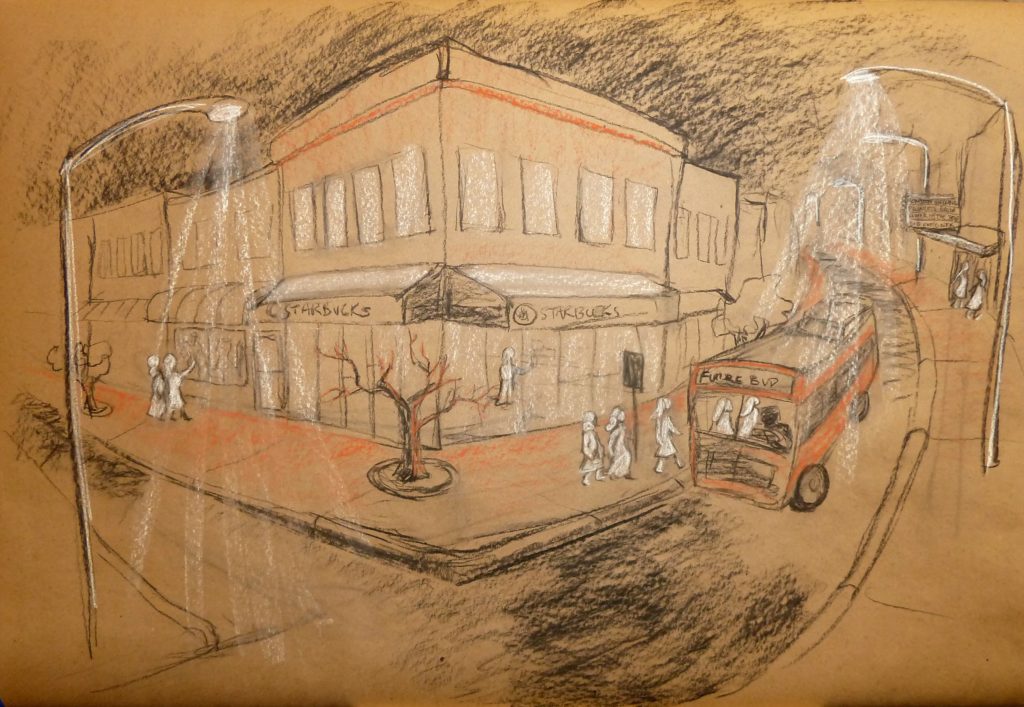

Naomi’s drawing is one of my favorites. Rather than a wedding, the ten women have been waiting for a bus to “Future Boulevard.” The five wise women are climbing onto the bus. The five unwise women are scattered about the neighborhood: two window shopping, one buying coffee, and two at the door of a move theater. (The wedding theme of the four movies playing reminds us of the original setting.) The barren fig tree stands, ignored, on the street corner.

More Barren Fig Tree Art

I didn’t find much Barren Fig Tree art: Two by usual suspects Jan Luyken (The Parable of the Fig Tree) and James Jacques Joseph Tissot (The Barren Fig Tree) and another by Steve Hammond (The Barren Fig Tree).

More Ten Bridesmaids Art

Art illustrating the Parable of the Ten Bridesmaids is more common, most of it highlighting the differences between the two sets of women.

- James B. Janknegt. The Wise and Foolish Bridesmaids (2003).

- William Blake. The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins (1822).

- Hieronymus Francken. Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins (c. 1616).

- Friedrich Wilhelm Schadow. The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins (1838–1842).

- Jan Adam Kruseman. The Wise and Foolish Virgins (1858).

- Pieter Brueghel. The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins.

- Gloria Ssali. Dinka Wise Virgins. (alternative version of Dinka Wise Virgins)

- Paul Delvaux. The Wise Virgins (1965).

- John Everett Millais. The Wise Virgins (1864).

- Ain Vares. The Parable of the Ten Virgins.

- Brother Mel. Five Foolish Virgins.

Music

For this class we sang “Where Is the Kingdom” (And Jesus Said #1), which includes a reference to the Parable of the Ten Bridesmaids (“It’s like those young women with oil in their lamps”); “Heav’n Is Like Ten Bridesmaids Waiting” (AJS #54); and “Keep Your Lamps Trimmed and Burning” (Singing the New Testament #47). And Jesus Said also includes another Bridesmaid song “Waiting for the Bridegroom” (AJS #53) and two Barren Fig Tree songs, “Jesus and the Fig Tree” (AJS #23) and “A Fruitless Fig Tree” (AJS #24).

This is the seventh post in a series about the Parables of Jesus Sunday school class I co-taught at Trinity CRC in Ames. In each post, I make a few observations about the parable, share Naomi Friend’s original artwork she drew during our class, post links to other art about the parable, and share our favorite songs about the parable. Previous posts covered the Parable of the Sower, The Parables of the Mustard Seed & the Leaven, The Parables of the Hidden Treasure and the Pearl of Great Price, The Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin, The Parable of the Lost Sons, and The Parable of the Wheat and the Weeds.